Spring season offers two must-see shows

Lucas Hnath's Dana H. and Matthew López's The Inheritance are as powerful as people say

This post is sponsored by CBC podcast PlayME, whose audio version of Matthew MacKenzie and Mariya Khomutova's First Métis Man of Odesa is ready to binge-listen to. The show is streaming in two parts, with a third part devoted to a fascinating interview with the writer/performers. See more below.

Forget, for the time being, all those stories – like this one or that one – you've likely read about how live theatre is on the brink of collapse. Two of the most powerful shows I expect to see this year are currently playing, and if you love this art form you need to see them while you still can. (Both close April 14.)

Dana H. (Rating: ✭✭✭✭✭), by Lucas Hnath, is the shorter of the two, at 75 minutes, and so it's probably the easier sell, even though there's nothing easy about it. In the weeks since I saw it, it's haunted me. When I discuss the show with others, it's as if we're trying to piece together some traumatic event we both witnessed but can't quite believe or comprehend.

Back in 1997, when Hnath was a student at NYU, his mother, Dana Higginbotham, was abducted by Jim, an Aryan Brotherhood member she'd met and helped in the psych ward of a Florida hospital where she worked as a chaplain. Perhaps because of some kindness she showed him one Christmas, or his own particular psychopathology, when Jim was released, he ended up knocking on the door of her home. When she wouldn't let him in, he broke in and whisked her away, ushering in what she calls "the beginning of the end."

For the next five months, Jim held Dana captive in a series of cars and motels, abusing her physically, sexually and emotionally. Why didn't Dana simply leave? Jim's underground network was spread out all over the American southeast. Even police officers were limited in what they could do, knowing that with his connections they'd be in danger themselves – and besides, he'd be out on the streets soon after being taken into custody.

Beyond that, though, Dana suggests that her own dysfunctional childhood and upbringing prepared her for this kind of behaviour – and maybe Jim, like any abuser, could sniff out her familiar, fearful wounds.

While this narrative is gripping on its own, the way Hnath and director Les Waters present the material is what makes it unique. Nearly two decades after the events, Hnath got director and writer Steve Cosson to interview his mother about that experience, which she had never recounted to her son.

Excerpts from this interview provide the spoken audio component of the play. At the beginning of the show, a stage manager outfits actor Jordan Baker with earbuds. And for the next hour and 15 minutes, Baker lip-syncs to that audio, recounting Dana's story.

It takes a few minutes to grasp this unusual concept. But Baker's gestures match up eerily with the voice we hear. Even the jangling of a bracelet, or a nervous smoothing down of a manuscript in her lap – an account of the events Dana H. had written down earlier – sync up with what we're hearing.

Hyper real performance

The result is a performance that's almost hyper real, stripped of artifice and unnecessary gestures. With most other confessional, fact-based solo shows – the one that springs to mind for some reason is Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking – we know an actor is embodying words on a page with her voice, physicality, emotional depth. Here, you see an actor, guided obviously by director Waters, digging deeply inside herself to authentically and spontaneously conjure the words she's "saying." More than that, she has to convince us where this voice is coming from – not just physically but emotionally and psychologically.

It's a high wire act performed in a simple, rather banal setting, and the contrast is terrifically effective. Designer Andrew Boyce captures the show's nondescript motel room so effectively you can practically smell the room's mix of mildew and Febreeze.

Of course, memories are subjective. And as with any first-person account, whether real or fictional, we occasionally question the veracity of what we're hearing. Some of the show's most remarkable moments involve Dana pausing, as if paralyzed, Baker's body suggesting the pain of trying to remember (or forget?) something. Baker/Dana's nervous laughter recounting something horrific or reliving moments are also telling.

Hnath has taken hours of interviews – taped over several days – and shaped them into something with a firm, satisfying structure. Edits are indicated by a couple of beeps. Beyond the facts of Dana's abduction, we piece together a subtle indictment of several institutions. There's the corrupt law enforcement system, for one. And after Dana admitted to her employer that she and her husband were getting divorced, she is fired from her job because it's a Catholic institution. This, keep in mind, leaves her isolated and vulnerable to Jim's later attack.

Baker, with absolutely nowhere to hide, ensures the experience isn't just a glorified radio interview. We know, by looking at her, that these things didn't happen to her – there's a remove. But what she allows us to do is experience the harrowing story with her and through her. This play has made me think not just about truth, memory and the aftereffects of trauma but also the purpose and meaning of acting.

Obviously, the real Dana H. would not be able to recount this tale six or seven times a week. But a great performer can do that.

And lest you think the show simply consists of a woman sitting in a chair in a room for 75 minutes (I mean, it is that in one sense), two of the most unforgettable images show us something else. One consists of Dana looking out the curtains of her motel room – remembering her ordeal? Thinking of past and/or future escapes? The other is a quiet moment that cleverly indicates the passing of time but also does something more.

A motel worker enters, tidies up the room and strips and changes the bedding. What she sees there doesn't faze her at all. She must see things like this all the time. In a show that's filled with horrors, this might be the most devastating horror of all.

Crow's Theatre's presentation of the Goodman Theatre, Center Theatre Group and Vineyard Theatre Production of Dana H. continues at the Factory Theatre Mainspace, 125 Bathurst, until April 14. See info here

The Inheritance pays huge dividends

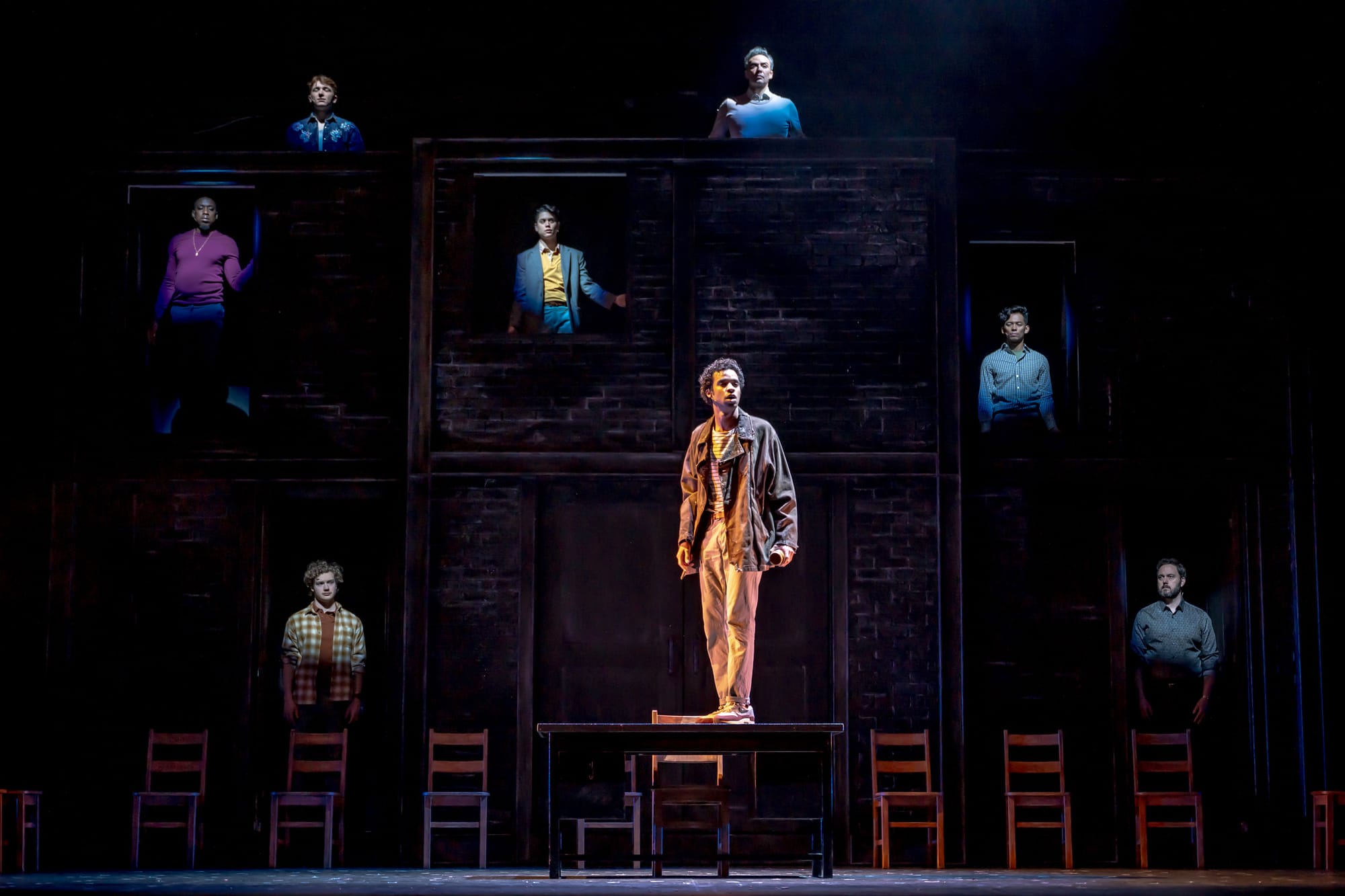

Brendan Healy's staging for Canadian Stage of Matthew López's epic play The Inheritance (Rating: ✭✭✭✭✭) offers up so many pleasures it's almost orgiastic.

Among the pleasures are: watching an absorbing, multilayered story play out artfully and entertainingly over nearly seven hours; witnessing a multi-generational acting ensemble triumph in a major new play; seeing Canadian Stage artistic director Healy make his Bluma Appel directing debut with the kind of confidence he's brought to smaller stages; and admiring a largely queer, refreshingly diverse cast get to play (mostly) contemporary queer characters pondering the idea of legacy and inheritance.

Any one of these things would be welcome enough on a Toronto stage. Seeing all of them in one two-part show amounts to an event.

Thirty-something New Yorkers Eric Glass (Qasim Khan) and Toby Darling (Antoine Yared) have been living together for years in the spacious, rent-controlled Upper West Side apartment Eric inherited from an aunt. During one of their at-home brunches with their queer friends, a precocious younger man named Adam (Stephen Jackman-Torkoff) shows up at their door with a Strand tote bag he'd mixed up with Toby's earlier that day at the iconic bookstore.

Soon, Adam finds his life intersecting with Eric and Toby's; an aspiring actor, he auditions for the stage adaptation of Toby's first novel.

Eric, meanwhile, has formed a bond with his neighbour and acquaintance Walter (Daniel MacIvor), an older gay man who lives with his partner Henry Wilcox (Jim Mezon). Eric has also recently learned that he's about to be evicted from his apartment; he hasn't yet told Toby.

Those are some of the narrative strands from the first part of the play. What I haven't yet mentioned is that López has borrowed liberally from E.M. Forster's novel Howards End for his play's plot and themes. Not only that, but Forster himself hovers on the edges of the play as Morgan, a guiding spirit, mentor and narrator (he's also played by MacIvor).

The A Room With a View and A Passage to India author's presence here is key. Although he died at 91 in 1970, a year after the Stonewall Riots, he never "came out," except perhaps to his Bloomsbury Group friends like John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf. (Homosexuality was illegal in the UK until 1967.) He finished his gay-themed novel Maurice, "Dedicated to a Happier Year," in 1914, but ensured it wasn't published until after his death.

López takes all of this and uses it as a jumping off point for his play. What, he makes us wonder, would Forster think of queer people a century after he wrote his prescient novel? What would Howards End, a novel about spiritual kinship, legacy and class differences, look like in today's world of hookup apps, PrEP and Log Cabin Republicans? And, perhaps most important of all, what have today's queer people learned from the sacrifices of earlier generations, particularly those who died during or survived the AIDS epidemic?

Although filled with ideas, this is a very funny play

What's so impressive is how gracefully López sets his various plots in motion. He uses Morgan to prod the central characters to tell their own stories, and they do, often narrating their actions in the third person. Any formality this lends to the proceedings is leavened by moments of wit and irony. This is a very funny play.

And while the work is filled with ideas, it's also got several gripping storylines that will keep you comparing notes with fellow audience members during each part's two intermissions. (One revelation in Part 2 elicited gasps.)

The cavernous Bluma Appel stage can dwarf many plays, but the ambition, scope and size of The Inheritance feel right at home here. Most of Michael Gianfrancesco's set consists of a brick backdrop and a series of wooden chairs and tables – perhaps suggesting the backstage of a theatre – but Healy's staging, Kimberly Purtell's lighting and Richard Feren's sound design transform each scene so we know whether we're in a tony Manhattan apartment or a dark corner of a back room in Fire Island.

It's a shame that López has mostly left the stage for TV and film. His characters' psychological depth and the imaginative way he interweaves their stories are hugely impressive.

What Healy and his cast have achieved is equally brilliant. Casting MacIvor, who's one of Canada's queer theatre pioneers (I wrote about that here), is a meta-theatrical gamble that pays off consistently. Sure, his British accent wavered a bit on the play's opening nights, but he's got the dramatic heft, gravitas and body of groundbreaking work to play a symbolic mentor to some ten younger artists.

Khan and Yared deliver performances that are so complex that you'll be reassessing their characters' motivations during the four intervals. Did Eric not tell Toby about losing the apartment because he was afraid the latter would leave him? I especially appreciated how all-in Yared is in making his character unlikeable yet magnetic. And Jackman-Torkoff creates such distinct and moving portraits of two lonely, younger gay men that when they have a brief scene together you readily accept it.

Standouts in the ensemble include Brenton Lalama's quippy Jason 2, Salvatore Antonio's blunt, principled businessman Jasper and his bro-ey double act, with Gregory Prest, as Henry Wilcox's two straight sons.

Most of the ensemble watches on during the scenes they're not in. In a way, they're witnesses. And so too are we. Nowhere is this more evident than in the moving, deeply felt conclusion to the play's first part. The scene was handled more gracefully when I first saw it on Broadway, but it's still a powerful moment, one that – like much of the show – could only happen at the theatre.

The Inheritance, Parts 1 and 2, continues at the Bluma Appel Theatre, 27 Front East, until April 14. See info here.

Dora-winning drama comes to PlayME podcast

If you missed the original Toronto run of First Métis Man of Odesa, it's returning next month as part of Soulpepper's season. Before then, though, you can catch CBC PlayME's excellent audio version of the show, available in its entirety here.

The play ran in Toronto a year ago, successfully criss-crossed the country and in between won Doras for outstanding new play, production and direction.

Written and performed by real-life couple Matthew MacKenzie and Mariya Khomutova, First Métis Man works remarkably well in audio – not surprising considering it began life as a short audio drama for Factory Theatre's You Can't Get There From Here series a year into the pandemic. Of course, that version only included the first half of the pair's tale of love, art, separation during a deadly pandemic. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February of 2022, they faced a whole new set of life-changing obstacles.

While I miss Daniela Masellis's set designs and Amelia Scott's projections, especially in the way they illustrate a recurring motif about travelling the world, other things come nicely into focus. Khomutova's layered performance feels especially intimate. Her account of one episode in the life of one of her theatre friends after Putin invaded is so vivid we see the scene in our imaginations.

The end of the play's first part – it was performed live without an intermission – delivers such a cliffhanger you'll definitely want to keep listening. And the sound design helps enhance the material, particularly in one effective scene late in the play when Matt falls out of his son's crib.

As always, PlayME's playwright interviews remain one of the best aspects of the podcast. The writer/performers are especially insightful about cultural stereotypes they heard from friends and colleagues. Khomutova tells interviewer Laura Mullin that playwrights have a lowly status in Ukraine (compared to actors and directors). And in one of the most moving sections, Khomutova discusses how writing the play helped save her from despair and a possible depression.